Ecocomics Explains is a new recurring feature of this blog. Each week, we will discuss a different economics concept--ranging from more basic ones to more advanced and mathematically involved ones--and highlight some examples from comic books that reflect the ideas.

We will also include a rating system in each post to show the difficulty level of the concepts. 1 Greenspan refers to a very basic concept, 2 Greenspans refers to a more intermediate concept and 3 Greenspans refers to an advanced concept.

(1 Greenspan)

Opportunity cost is a fairly basic economics concept. Anyone who has taken any introductory microeconomics course certainly knows about it. It is usually one of the first topics introduced in class. You're probably familiar with a number of classic examples, such as having a choice between hamburgers and pizza or guns and butter. Those of you who have never taken economics before are still likely familiar with the intuition behind it, but maybe not know the terminology.

Opportunity cost stems from the fact that resources are scarce. In fact, the entire field of economics is basically the study of how individuals and societies allocate scarce resources. When a society chooses to place greater emphasis on the production of one good, then production of another good necessarily has to decrease. Similarly, consumers who have a fixed income have to make choices between which goods to buy. Purchasing more of one means purchasing less of another. The opportunity cost of a good, then, is what an individual, firm or society gives up in order to have one particular good. It is the value of the highest valued foregone alternative (this is the definition used in the third edition of

Microeconomics Michael L. Katz).

This doesn't just apply to production and consumption of goods, however. It embodies the idea of tradeoffs, which is something that we all experience on a daily basis. And it happens in comic books all the time too!

To see how this works, let's consider the case of Spider-Man. Spidey is a fascinating study because basically the entire point of his ongoing series is to highlight his struggle to maintain a balance between his personal life and his obligations as a superhero. Every day for Spider-Man is an exercise in opportunity costs.

The Amazing Spider Man #600 by Dan Slott and John Romita Jr. (2009)

The Amazing Spider Man #600 by Dan Slott and John Romita Jr. (2009)

See here how Peter Parker is making a choice between earning some more money to support his crime-fighting double life and attending Aunt May's rehearsal dinner (she was recently married to J. Jonah Jameson senior). Let's look at this example in a bit more detail, but spice it up a bit. Suppose that Peter has 60 minutes (1 hour) of free time. In that free time, he can either go out and fight some thugs on the street or he can choose to attend Aunt May's rehearsal dinner and spend time with his family. Also, let's say that it takes Spider-Man 12 minutes to take down an ordinary street thug and that it takes 6 minutes with his family to earn him a "brownie point." This means that Spider-Man has a production equation of the form:

12x + 6y = 60

where x is the number of criminals Spider-Man takes down and y is the number of brownie points he earns at the May residence. Given this equation, if Spidey decides to take down 3 thugs (x=3), then we have:

12(3) + 6y = 60

36 + 6y = 60

6y = 24

y = 4

Thus, if Spider-Man spent his hour taking down 3 thugs, he could have also had the time to earn 4 brownie points.

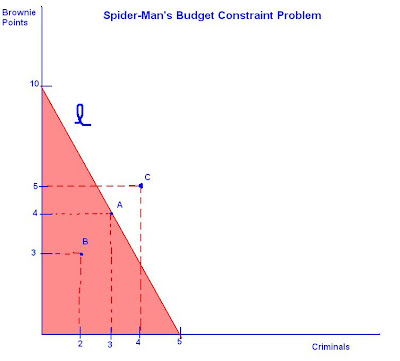

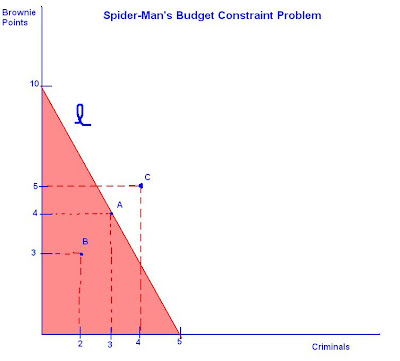

This can be represented graphically as follows:

Note: Not Drawn to Scale. Not drawn particularly well either. By now you've noticed, I prefer drawing my graphs in MS Paint. Lost art, really.

Note: Not Drawn to Scale. Not drawn particularly well either. By now you've noticed, I prefer drawing my graphs in MS Paint. Lost art, really.In the graph above, line "l" represents Spider-Man's "budget constraint." This is just a visual representation of the bundles of goods that our webcrawler can "afford" with his given "income." In this case, income refers to Spider-Man's allotted time schedule, the goods are brownie points and criminals put in jail, and costs refers to time in minutes. Any point on the graph beneath line "l" is in Spider-Man's "feasible set." This is the set of all combinations of criminals and brownie points that Spider-Man can possibly afford in his hour of free time. Any point that is in the pink shaded area of the graph is feasible.

Take our example above. If Spider-Man chooses to fight 3 thugs, which would take 36 minutes, he could then only earn 4 brownie points. This is reflected as point A on the graph. Notice that point A is exactly on the budget line. Hence, Spider-Man is using

all of his time towards one of the two goods. This is an efficient use of his time. Suppose instead that Spider-Man decided to fight 2 criminals and earn 3 brownie points (point B of the graph). In minutes, the bundle would cost:

12(2) + 6(3) = 24 + 18 = 42 minutes.

Point B, although being in the feasible set, is

not efficient. The reason is that Spider-Man is only using 42 minutes of his time, which means he has 18 minutes left over that are not being devoted to one of the two goods that exists in this universe. With that 18 minutes, he could be fighting more criminals or earning more brownie points. But he isn't.

Now consider point C of the graph. At this point, Spider-Man fights 4 thugs and earns 5 brownie points. In minutes, this bundle would cost:

12(4) + 6(5) = 48 + 30 = 78 minutes.

Obviously, Spider-Man only has 60 minutes and therefore cannot purchase this bundle of goods. Point C is therefore not feasible.

If Spidey chose not to attend Aunt May's dinner at all, but instead to spend the entire hour fighting crime, he would be able to bring down a maximum of 5 street thugs in the 60 minutes. If he chose to sacrifice his hero duties for an hour and spend its entirety with the family, he would be able to earn a maximum of 10 brownie points. These points are the x and y intercepts of the graph and are the endpoints of the budget constraint.

So, where is Spider-Man's opportunity cost in this graph? It's actually the slope of the budget line! Notice that the slope is -2. This represents the opportunity cost of one good in terms of the other. So, the opportunity cost of one criminal is 2 brownie points. To put one more criminal to justice,

Spider-Man would have to sacrifice 2 brownie points that he would have otherwise gained by being with his family. Conversely, to gain two more brownie points, Spider-Man would have to sacrifice fighting 1 criminal.

Those are the basics of opportunity cost in a nutshell. I even threw in a little bit of linear budget constraints. Once we discuss utility maximization, we can bring in other factors. For example, we all know that Spider-Man suffers from immense guilt over the death of Uncle Ben and would likely derive more utility from fighting a criminal than maintaining his personal life. We can factor all (or most) of this in to an optimization problem. But this is a post for another time.

(1 Greenspan)

(1 Greenspan) The Amazing Spider Man #600 by Dan Slott and John Romita Jr. (2009)

The Amazing Spider Man #600 by Dan Slott and John Romita Jr. (2009) Note: Not Drawn to Scale. Not drawn particularly well either. By now you've noticed, I prefer drawing my graphs in MS Paint. Lost art, really.

Note: Not Drawn to Scale. Not drawn particularly well either. By now you've noticed, I prefer drawing my graphs in MS Paint. Lost art, really. Amazing Spider-Man #610 by Marc Guggenheim, Marco Checchetto, Luke Ross and Rick Magyar (2009)

Amazing Spider-Man #610 by Marc Guggenheim, Marco Checchetto, Luke Ross and Rick Magyar (2009)